Emily Reid

I help people reduce and control their tics and take control of their anxiety.

Understanding the Neurological Process of Tics

April 17, 2025

I see a lot of clients of different ages and in different locations, and I consistently hear that no one has ever really explained how tics happen in the brain and body. I feel strongly that education makes a world of difference in understanding what’s happening to you but also giving you a sense of control over a condition that is described as involuntary. I hope to bridge that gap in knowledge for you so you feel more empowered and can educate friends and family members.

The Neurological Root

Tic disorders, including Tourette Syndrome and chronic motor or vocal tic disorders, are often misunderstood as purely behavioral or psychological issues. In reality, tics have a strong neurological basis. These involuntary, repetitive movements or sounds are rooted deep within the brain’s motor control systems. Understanding what’s happening beneath the surface can reduce stigma and empower those affected with knowledge.

What Are Tics?

Tics are sudden, rapid, recurrent movements or vocalizations that a person feels the urge to do. They can range from simple (like eye blinking or throat clearing) to complex (like jumping or saying word/phrases). People with good awareness of their tics often describe an urge or tension that builds up—like an itch needing to be scratched—until the tic is released.

The Brain Regions Involved

Tics arise from abnormalities in a network of brain areas responsible for motor control, particularly the Cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) circuits or the “motor pathway” of the brain. This feedback loop between different brain regions helps control voluntary and involuntary movements. In tic disorders, this loop is disrupted or “glitches” leading to the involuntary motor or vocal tic:

- The Basal Ganglia: This group of structures deep within the brain helps regulate movement initiation and inhibition. In tic disorders, this system appears to be overactive or dysregulated, leading to unwanted movements.

- The Thalamus: Acting as a relay station, the thalamus helps direct sensory and motor signals. In people with tics, it may fail to properly filter signals, allowing inappropriate motor commands to go through.

- The Cortex: The motor and prefrontal areas of the brain are involved in planning and executing movements. Studies suggest these regions may be “over-engaged” in tic disorders, possibly due to an overactive feedback loop between the cortex and subcortical structures.

Why Do Tics Fluctuate?

Tics often wax and wane in intensity, and stress, excitement, or fatigue can make them worse. This is likely because emotional states influence the brain’s motor circuits and neurotransmitter levels. External triggers can also influence an emotional state which will trigger tics. For example, a loud, crowded environment can make a person overwhelmed or irritated and that will trigger a tic onset. People may also suppress tics in certain settings, which can make them return more forcefully later.

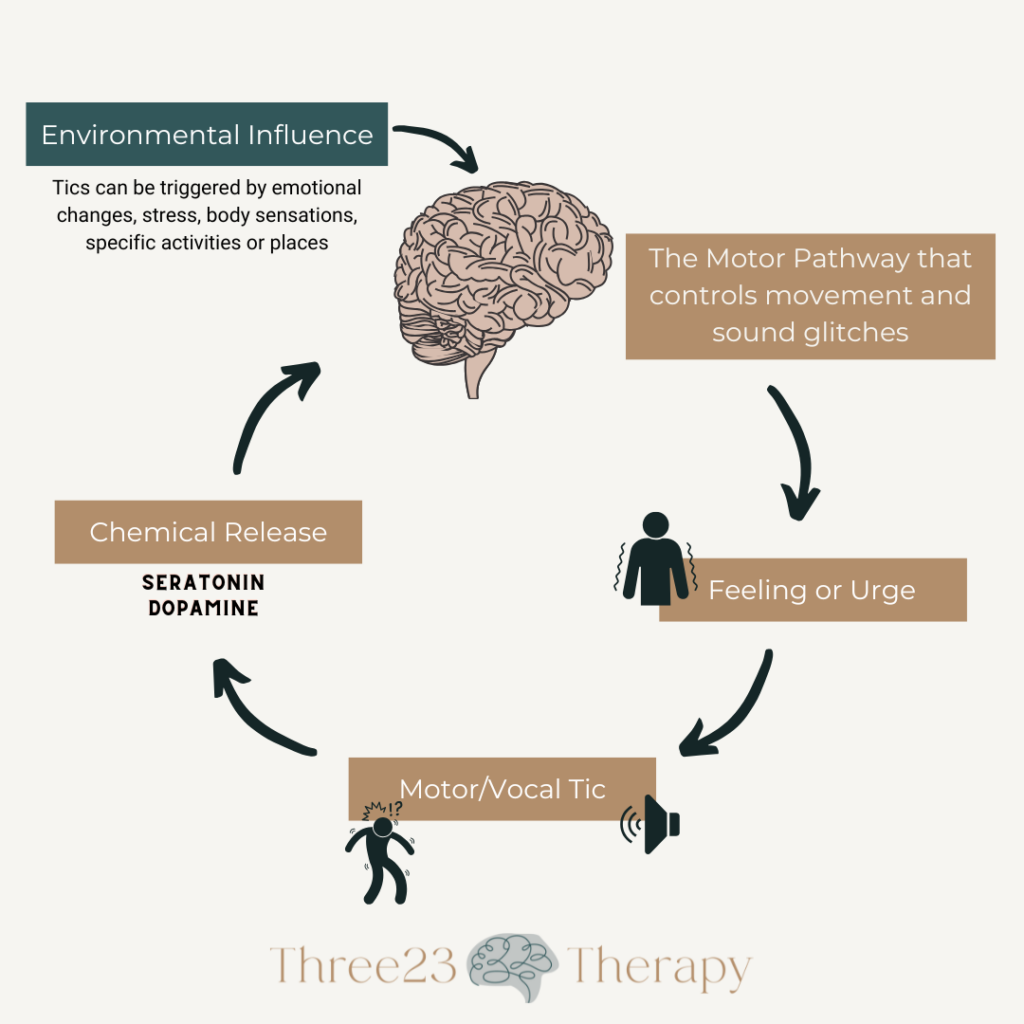

The Visual Cycle

This visual guide from explains the basic neurological and behavioral cycle of how motor and vocal tics occur. The process is broken down into key stages:

- Motor Pathway Glitch

- The brain’s motor pathway, which normally controls movement and sound, experiences a disruption or “glitch.” This leads to irregular signals being sent to the body, setting the stage for a tic.

- Warning Signal or Urge

- A person experiences a premonitory urge or internal signal that a tic is coming. This can feel like tension, pressure, or a buildup that needs to be released.

- Motor/Vocal Tic

- The individual performs a tic—either a movement (motor tic) or a sound (vocal tic). This is an involuntary response to the urge.

- Chemical Release

- After the tic is performed, the brain releases neuro-chemicals such as dopamine and serotonin. This chemical release provides a momentary feeling of relief or satisfaction, which reinforces the tic behavior.

- Environmental Influence

- Both internal (thoughts, emotions, fatigue) and external (surroundings, social context, stress) factors can influence the frequency and intensity of tics. The visual illustrates that this cycle repeats itself, particularly when environmental triggers are present.

Underlying Causes for Tic Development

Genetic Factors

- Tic disorders often run in families, suggesting a strong genetic component.

- No single “tic gene” has been identified, but multiple genes likely contribute to vulnerability.

- Genetic links have also been found with related conditions like ADHD and OCD, which often co-occur with tics.

Environmental and Developmental Factors

- Prenatal and perinatal events: Complications during pregnancy or birth, low birth weight, and c-sections have been associated with a higher risk.

- Infections and immune responses:

- Infections (like strep) have been linked to sudden-onset tics, particularly in a condition known as PANDAS (Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal infections).

- Though not fully understood or confirmed, some researchers are exploring the role of autoimmune encephalitis, multiple sclerosis, or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in causing tic-like symptoms due to inflammation in specific brain regions. However, these are rare and usually accompanied by other more prominent neurological symptoms.

- Stress and anxiety:

- These don’t usually cause tics, but they often worsen them. Emotional states can affect the brain’s motor circuits and neurotransmitter levels. However, extremely high levels of anxiety can lead to Functional Neurological Disorder (FND), and tics can be a symptom of FND.

Trigeminal Nerve Dysfunction

- The trigeminal nerve is the largest cranial nerve, and it’s responsible for carrying sensory information from the face to the brain, including sensations like touch, pressure, pain, and temperature. It also controls certain motor functions like jaw movement.

- When this nerve isn’t functioning properly—due to irritation, hypersensitivity, or inflammation—it can contribute to or trigger motor tics, especially those involving the face, head, or neck.

The Role of Habit Loops and Brain Plasticity

Over time, the brain can “learn” the tic cycle—urge, tic, relief—and reinforce it, turning tics into habitual motor patterns. This is where Comprehensive Behavioral Intervention for Tics (CBIT) come in, helping retrain the brain to respond differently to the pre-tic urge through strategies called competing responses. I have another blog post on “CBIT THERAPY VERSUS SUPPRESSING TICS” that describes how CBIT works.

Thanks for reading!

Understanding the neurological and physiological roots of tics can help reduce stigma and lead to more compassionate, effective support. Whether you’re a parent, educator, or someone living with tics, know that knowledge is a powerful step toward healing and resilience.

If you found this post helpful, feel free to share it—and be sure to check back for more insights on the brain, behavior, and evidence-based tools for thriving.

Download our free guide: Understanding Your Child’s Tics

A clear, parent-friendly resource to help you make sense of what you’re seeing.

👉 Learn more about CBIT therapy at Three23 Therapy

Explore how evidence-based support can help your child feel more in control.

Peace and Blessings,

Emily, OTR/L

Occupational Therapist

emily@three23therapy.com

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Tic Presentation Checklist

A practical guide to help families, educators, and providers distinguish between typical and functional tics and support informed decisions about care and treatment

Tic Symptom Checklist

A comprehensive checklist to track motor and vocal tics, related behaviors, and patterns to support monitoring and communication with healthcare providers.

Supporting Students in School

A parent-friendly guide to help teachers understand tics, respond appropriately, and implement classroom strategies that support students’ learning and well-being.